Understanding Ethereum Smart Contract Storage

Ethereum smart contracts use an uncommon storage model that often confuses new developers. In this post, I’ll describe that storage model and explain how the Solidity programming language makes use of it.

One Astronomically Large Array

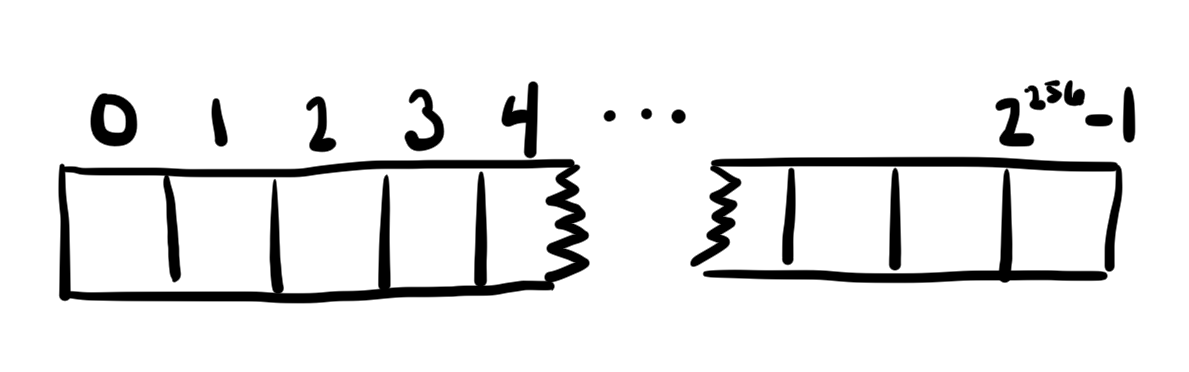

Each smart contract running in the Ethereum Virtual Machine (EVM) maintains state in its own permanent storage. This storage can be thought of as a very large array, initially full of zeros. Each value in the array is 32-bytes wide, and there are 2256 such values. A smart contract can read from or write to a value at any location. That’s the extent of the storage interface.

I encourage you to stick with the “astronomically large array” mental model, but be aware that this is not how storage is implemented on the physical computers that make up the Ethereum network. Storage is extremely sparsely populated, and there’s no need to store the zeros. A key/value store mapping 32-byte keys to 32-byte values will do the job nicely. An absent key is simply defined as mapping to the value zero.

Because zeros don’t take up any space, storage can be reclaimed by setting a value to zero. This is incentivized in smart contracts with a gas refund when you change a value to zero.

Locating Fixed-Sized Values

In this storage model, where do things actually go? For known variables with fixed sizes, it makes sense to just give them reserved locations in storage. The Solidity programming language does just that.

contract StorageTest {

uint256 a;

uint256[2] b;

struct Entry {

uint256 id;

uint256 value;

}

Entry c;

}

In the above code:

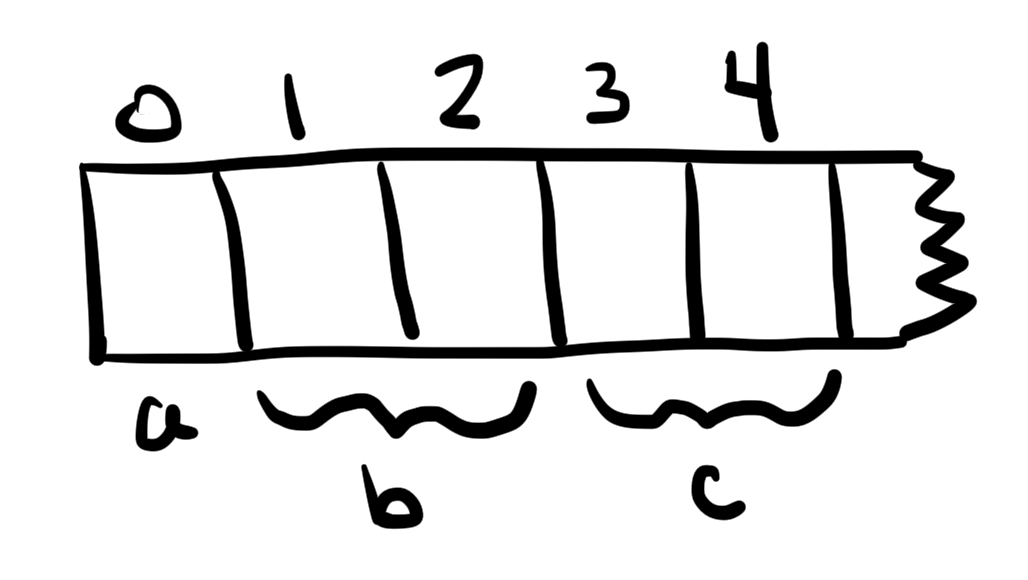

ais stored at slot 0. (Solidity’s term for a location within storage is a “slot.”)bis stored at slots 1, and 2 (one for each element of the array).cstarts at slot 3 and consumes two slots, because theEntrystruct stores two 32-byte values.

These slots are determined at compile time, strictly based on the order in which the variables appear in the contract code.

Locating Dynamically-Sized Values

Using reserved slots works well for fixed-size state variables, but it doesn’t work for dynamically-sized arrays and mappings because there’s no way of knowing how many slots to reserve.

If you’re thinking of computer RAM or hard drive as an analogy, you might expect that there’s an “allocation” step to find free space to use and then a “release” step to put that space back into the pool of available storage.

This is unnecessary due to the astronomical scale of smart contract storage. There are 2256 locations to choose from in storage, which is approximately the number of atoms in the known, observable universe. You could choose storage locations at random without ever experiencing a collision. The locations you chose would be so far apart that you could store as much data as you wanted at each location without running into the next one.

Of course, choosing locations at random wouldn’t be very helpful, because you would have no way to find the data again. Solidity instead uses a hash function to uniformly and repeatably compute locations for dynamically-sized values.

Dynamically-Sized Arrays

A dynamically-sized array needs a place to store its size as well as its elements.

contract StorageTest {

uint256 a; // slot 0

uint256[2] b; // slots 1-2

struct Entry {

uint256 id;

uint256 value;

}

Entry c; // slots 3-4

Entry[] d;

}

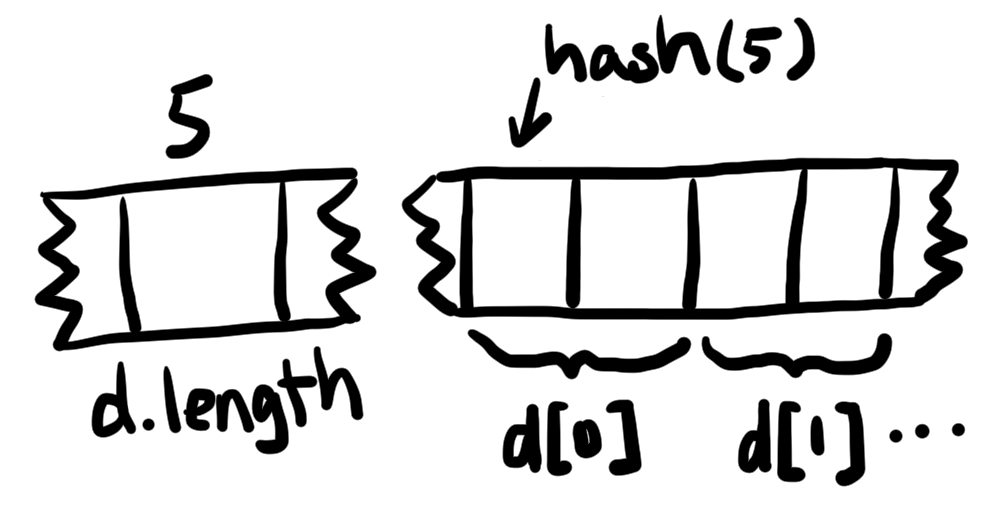

In the above code, the dynamically-sized array d is at slot 5, but the only thing that’s stored there is the size of d. The values in the array are stored consecutively starting at the hash of the slot.

The following Solidity function computes the location of an element of a dynamically-sized array:

function arrLocation(uint256 slot, uint256 index, uint256 elementSize)

public

pure

returns (uint256)

{

return uint256(keccak256(slot)) + (index * elementSize);

}

Mappings

A mapping requires an efficient way to find the location corresponding to a given key. Hashing the key is a good start, but care must be taken to make sure different mappings generate different locations.

contract StorageTest {

uint256 a; // slot 0

uint256[2] b; // slots 1-2

struct Entry {

uint256 id;

uint256 value;

}

Entry c; // slots 3-4

Entry[] d; // slot 5 for length, keccak256(5)+ for data

mapping(uint256 => uint256) e;

mapping(uint256 => uint256) f;

}

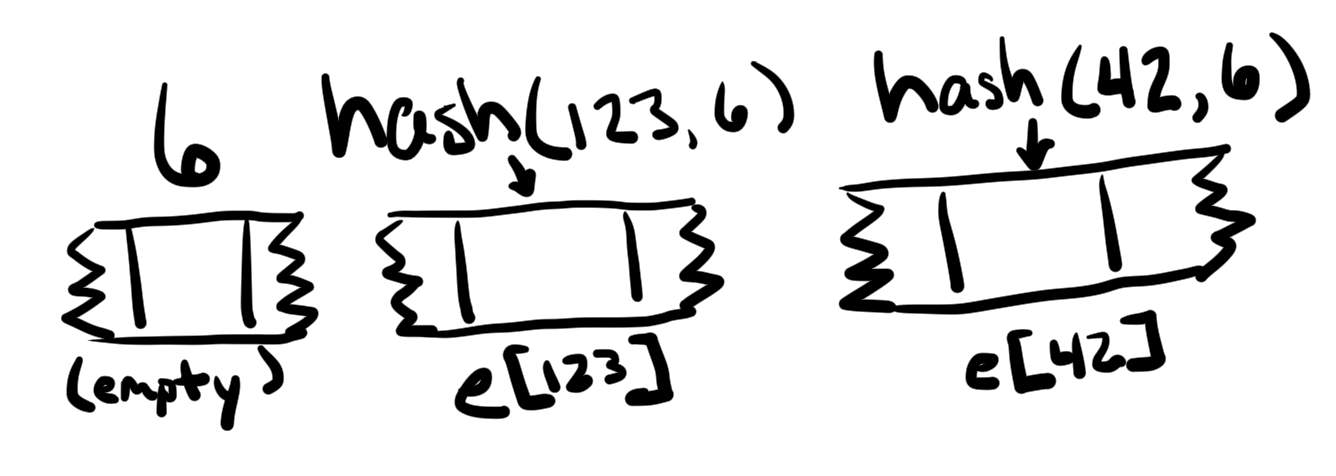

In the above code, the “location” for e is slot 6, and the location for f is slot 7, but nothing is actually stored at those locations. (There’s no length to be stored, and individual values need to be located elsewhere.)

To find the location of a specific value within a mapping, the key and the mapping’s slot are hashed together.

The following Solidity function computes the location of a value:

function mapLocation(uint256 slot, uint256 key) public pure returns (uint256) {

return uint256(keccak256(key, slot));

}

Note that when keccak256 is called with multiple parameters, the parameters are concatenated together before hashing. Because the slot and key are both inputs to the hash function, there aren’t collisions between different mappings.

Combinations of Complex Types

Dynamically-sized arrays and mappings can be nested within each other recursively. When that happens, the location of a value is found by recursively applying the calculations defined above. This sounds more complex than it is.

contract StorageTest {

uint256 a; // slot 0

uint256[2] b; // slots 1-2

struct Entry {

uint256 id;

uint256 value;

}

Entry c; // slots 3-4

Entry[] d; // slot 5 for length, keccak256(5)+ for data

mapping(uint256 => uint256) e; // slot 6, data at h(k . 6)

mapping(uint256 => uint256) f; // slot 7, data at h(k . 7)

mapping(uint256 => uint256[]) g; // slot 8

mapping(uint256 => uint256)[] h; // slot 9

}

To find items within these complex types, we can use the functions defined above. To find g[123][0]:

// first find arr = g[123]

arrLoc = mapLocation(8, 123); // g is at slot 8

// then find arr[0]

itemLoc = arrLocation(arrLoc, 0, 1);

To find h[2][456]:

// first find map = h[2]

mapLoc = arrLocation(9, 2, 1); // h is at slot 9

// then find map[456]

itemLoc = mapLocation(mapLoc, 456);

Summary

- Each smart contract has storage in the form of an array of 2256 32-byte values, all initialized to zero.

- Zeros are not explicitly stored, so setting a value to zero reclaims that storage.

- Solidity locates fixed-size values at reserved locations called slots, starting at slot 0.

- Solidity exploits the sparseness of storage and the uniform distribution of hash outputs to safely locate dynamically-sized values.

The following table shows how storage locations are computed for different types. The “slot” refers to the next available slot when the state variable is encountered at compile time, and a dot indicates binary concatenation:

| Kind | Declaration | Value | Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simple variable | T v |

v |

v's slot |

| Fixed-size array | T[10] v |

v[n] |

(v's slot) + n * (size of T) |

| Dynamic array | T[] v |

v[n] |

keccak256(v's slot) + n * (size of T) |

v.length |

v's slot | ||

| Mapping | mapping(T1 => T2) v |

v[key] |

keccak256(key . (v's slot)) |

Further Reading

If you’d like to learn more, I recommend the following resources:

- The Solidity documentation covers the layout of state variables in storage.

- Howard’s excellent series on the EVM includes two relevant parts: Storage Layout and The Hidden Costs of Arrays