State Channels for Two-Player Games

This post will introduce the concept of state channels in the context of a two-player game. I’ll enhance the contract from Two-Player Games in Ethereum to support making moves in the game without sending transactions. By avoiding on-chain transactions, the new game will be faster and less expensive.

What is a State Channel?

State channels are a very broad and simple way to think about blockchain interactions which could occur on the blockchain, but instead get conducted off of the blockchain, without significantly increasing the risk of any participant.

–Jeff Coleman, 2015

The preceding quote is from Jeff Coleman’s excellent post State Channels, which is the best introduction to state channels that I’ve seen. I encourage you to take a few minutes to read it in its entirety.

The technology behind state channels should be familiar to readers of this blog. We’ve previously covered digital signatures, which allow participants to commit to state updates, and payment channels, which are a specific form of state channel. As with a payment channel, using a state channel consists of three steps:

- Opening the channel, often including some sort of escrow.

- Exchanging state updates off-chain using digital signatures.

- Closing the channel by providing the latest agreed upon state.

Applying State Channels to a Two-Player Game

The previous “21 game” contract used only on-chain transactions. This has the desirable property of making the game trustless. The contract enforces the rules of the game and guarantees the fairness of the outcome. However, transactions have downsides. Each transaction requires gas, and each transaction needs to be mined into a block, which takes time.

By using a state channel, we can avoid some of the transactions without sacrificing the trustlessness. Without a state channel, most of the transactions are players taking turns calling move(). With a state channel, each player will instead send signed messages indicating their moves directly to their opponent.

As long as the smart contract accepts such signed messages and updates the game state accordingly, the signed message is just as good as a transaction sent directly to the contract.

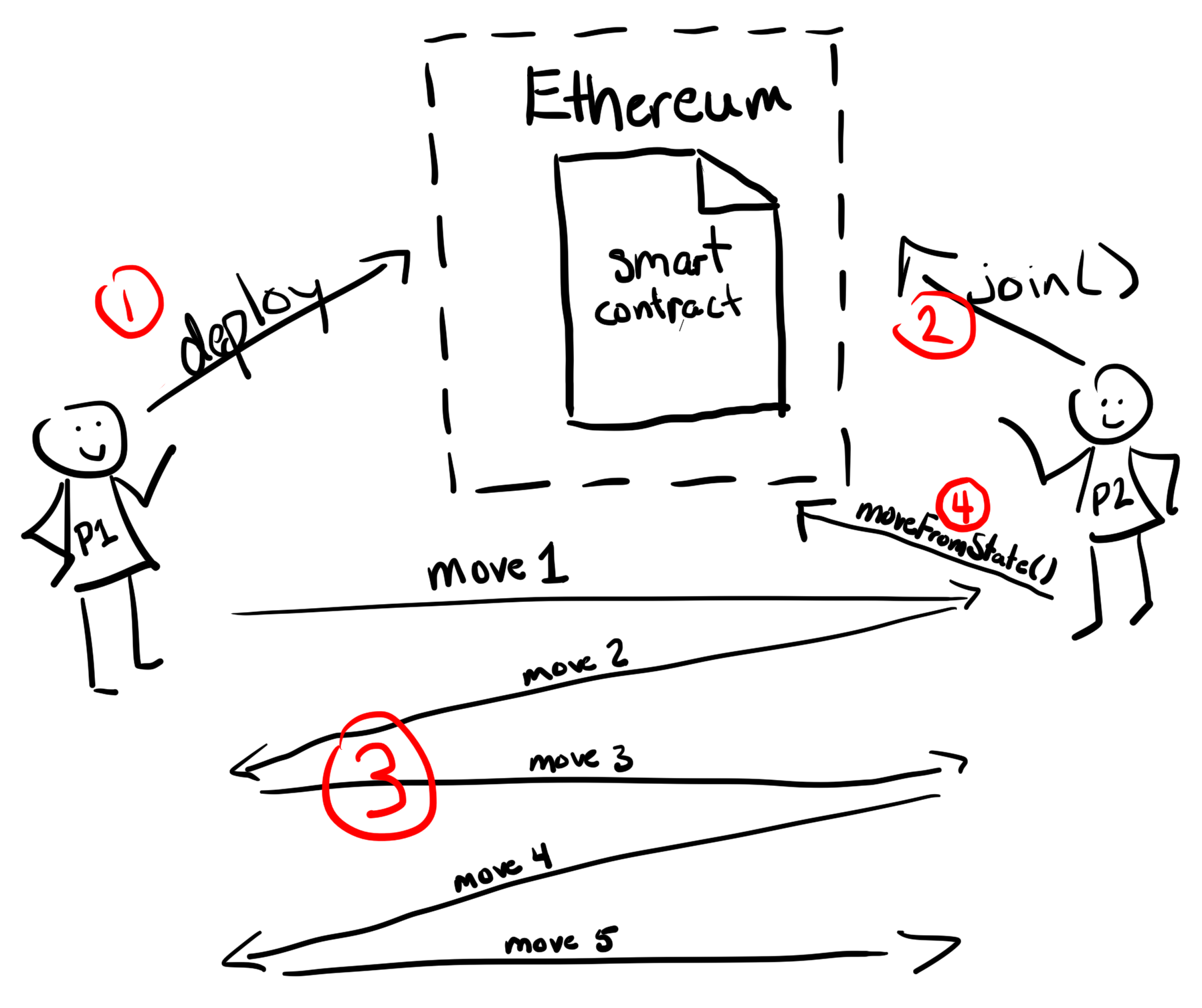

The typical steps using the state channel version of the contract are as follows:

- Player 1 deploys the contract (on chain).

- Player 2 joins the game (on chain).

- Players make moves by exchanging signed states (off chain).

- The winning player makes their final move based on a signed message from their opponent (on chain).

As compared to the previous version of the contract, calls to move() can be replaced with signed messages exchanged off chain, and a new moveFromState() function allows a player to make an on-chain move based on a signed message from their opponent.

Adding a Sequence Number

At any time, either player can send a recent signed message from their opponent to the smart contract. The opponent signed the state explicitly in a message, and the sender signed it implicitly by sending it in a transaction. Because both players have signed the message, it represents an agreement between the two players. This does not, however, mean that it is a new state.

To know if a state is new, state updates will include a sequence number that always increases. A state with a higher sequence number always takes precedence over a state with a lower sequence number. This makes it impossible for a player to cheat by trying to submit an old game state to the smart contract.

The previous contract already includes a GameState struct. I’ve added a sequence number called seq:

struct GameState {

uint8 seq;

uint8 num;

address whoseTurn;

}

When both players are cooperating and communicating directly, there’s no need to call move(), but the function still needs to be there to handle the case where one player stops sending signed messages. In that case, the fallback is for players to use on-chain transactions to move the game forward.

The move() function must increment the sequence number each time a move is made. I’ve also added the expected current sequence number as a parameter. This prevents a race condition where one player sends a move() transaction but by the time it arrives at the smart contract, the contract’s state has changed:

event MoveMade(address player, uint8 seq, uint8 value);

function move(uint8 seq, uint8 value) public {

require(state.seq == seq, "Incorrect sequence number.");

// ...

state.seq += 1;

// ...

emit MoveMade(msg.sender, seq, value);

}

Using a Signed State

The move() function allows a player to move based on the last state registered with the smart contract. With a state channel, though, the latest (off-chain) state is probably not known to the smart contract. To make an on-chain move from an off-chain state, the player must present that state to the smart contract, signed by their opponent:

function moveFromState(uint8 seq, uint8 num, bytes sig, uint8 value) public {

require(seq >= state.seq, "Sequence number cannot go backwards.");

bytes32 message = prefixed(keccak256(address(this), seq, num));

require(recoverSigner(message, sig) == opponentOf(msg.sender));

state.seq = seq;

state.num = num;

state.whoseTurn = msg.sender;

move(seq, value);

}

A brief explanation of the code above:

- The parameters

seqandnumrepresent the state signed by the opponent. ThewhoseTurnvalue is implicit; if player 1 signs a state, it is by definition now player 2’s turn. - The signature is checked using

prefixed()andrecoverSigner(), which are borrowed from my post Signing and Verifying Messages in Ethereum. - The address of the contract is included in signed message to prevent cross-contract replay attacks as described in Signing and Verifying Messages in Ethereum.

- The contract’s game state is replaced with the signed state.

- Finally,

move()is called to apply the player’s move.

Although moveFromState() can be called at any time, it is usually only called once per game: to make the winning move and collect the wagered ether.

On-chain Fallback

Typically, game moves are made by exchanging signed messages rather than using on-chain transactions. However, in the case where one player stops sending signed messages—either as an attempt to stall the game or because of a communication problem—it’s important that players can fall back to using the smart contract.

Just as in the previous contract, if a player’s opponent has stopped making moves, the player needs to invoke a timeout by calling startTimeout(). For the smart contract to allow such a call, it must know the current game state—or at least whose turn it is. A player can first call moveFromState() to inform the smart contract of the latest agreed-upon state and to apply their latest move. This makes it their opponent’s turn and allows the timeout to be started.

In response to a timeout, the player whose turn it is must make a move by calling move(). This resets the timer and lets the game continue. Players can then resume the typical workflow of exchanging signed messages, or they can continue to make moves on chain.

Why Can the Sequence Number Stay the Same?

The requirement seq >= state.seq in moveFromState() may surprise you. Why doesn’t this read seq > state.seq?

Before answering the question, I’d like to establish two important invariants for the smart contract:

- Once a player has committed to a move in a signed message, they cannot undo that move. Otherwise, the game is not trustless.

- The sequence number increases with each move made. Otherwise, there’s no guarantee the game will end.

It seems at first that the combination of signed messages and the requirement seq > state.seq would take care of both invariants. However, consider the following scenario from a chess game:

- In the middle of the game, Alice makes a threatening move. She does this by sending Bob a signed message with a sequence number 15 and a complete game state.

- Bob responds by moving his queen. He signs a new message with the sequence number 16 and a new game state.

- Alice notices she can capture Bob’s queen with her knight. She does so by sending a message to Bob with sequence number 17 and a new game state.

- Bob, who is very unhappy to have lost his queen, does something tricky. He sends a transaction to the smart contract with Alice’s signed message at sequence number 15 and makes a different move (#16) than the one he previously sent to Alice.

After this, the sequence number the smart contract knows about is 16. Alice has a message from Bob indicating his original move, but she can’t use it, because its sequence number is also 16. This violates the first invariant, because Bob was able to undo a move he committed to.

Relaxing the requirement to seq >= state.seq takes care of this problem. Alice can submit Bob’s signed message with sequence number 16, forcing him to stick with his original move.

Even with the relaxed requirement, moveFromState() maintains the second invariant because the new move increments the sequence number.

Summary

- State channels enable off-chain signed messages to replace expensive on-chain transactions.

- Sequence numbers ensure that the smart contract will eventually know the latest state.

- The nature of a turn-based game means that the smart contract must force forward progress to be made. This leads to subtlety in how sequence numbers are treated.

- It’s important that an on-chain fallback exists for the case where off-chain communication breaks down.

Future Posts

I have not yet dealt with how end users would interact with a game based on a state channel. The next post in this series will show a JavaScript front end that takes care of the tricky business of signing and exchanging states and interacting with the smart contract as needed.